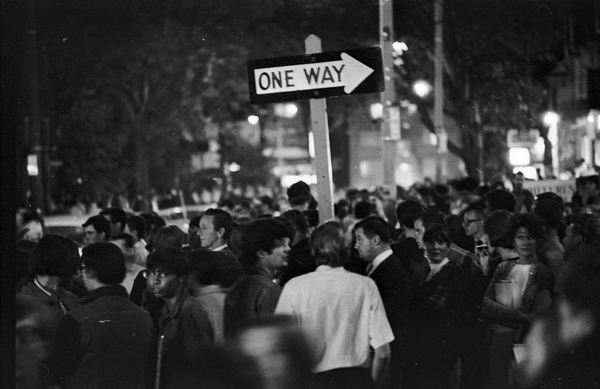

York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections, Toronto Telegram fonds, ASC00616

In the mid to late 1960s, "the future" for youth meant something radically different than it did for past generations. Their concept of what constituted meaningful community service had changed from the traditional models presented by historical antecedents ranging from the Jesuit missionaries of New France to the bush camps of Frontier College.[1] Youth rejected the present and the past by ignoring tradition and by exceeding limits. Their future was not to be a mere outgrowth and consolidation of what came before but it involved a complete break from and a negation of the past.[2]

The culture of youth in the sixties was populated with ideologues and activists as well as those who spoke loudly in the language of the anti-establishment scene. It was a sort of melting pot for student radicalism and the ideas of the New Left or a channel through which much of this energy was filtered. It was comprised predominantly, although not exclusively, of recent university graduates with many of its leaders coming to it with a history of student politics and a glossary of terms defined by that experience.

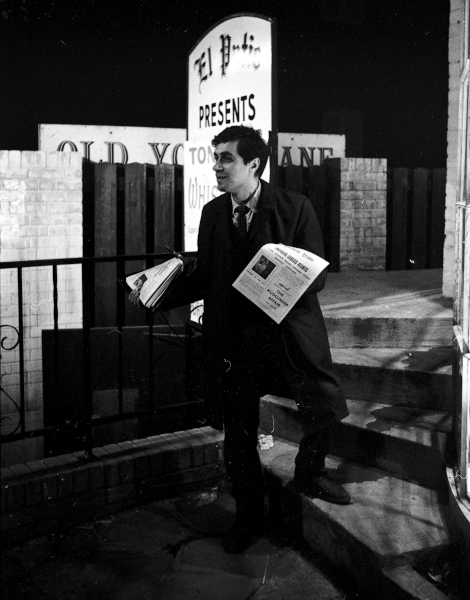

York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections, Toronto Telegram fonds, ASC00084

Youth of the day unfolded under the sign of beauty, harmony and joy. Misfortune had passed them by. If they looked behind them, all they saw were the years of war and deprivation experienced by their parents. They had a sense of innocence that was characterized by a limitless love of self and confidence in the value of their actions. They were aware of the power of their numbers and the power they had over life's circumstances. Their future was one filled with light and their desire for change was inspired by the rhetoric of radicalism, anti-Americanism and student power.[3]

The militancy of this generation was expressed on a daily basis and was increasingly galvanized during a darkening time when the older generation was seen as being responsible for atrocities including the assassination of Martin Luther King, the war in Vietnam and the invasion of Prague.[4] The full realization of their power through organization gave youth confidence in their strength and faith in the future. This spurred them on to make more and more radical demands of the society around them and to broaden their actions.[5] They began by demanding control of schools but ultimately wanted to take control of society, its institutions and the way it functioned, shared wealth and defined its goals. Youth had a hard time understanding anything in moderation especially when it came to politics.[6]

Citation: York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections, Toronto Telegram fonds, ASC00082

To François Ricard, author of The Lyric Generation: The Life and Times of the Baby Boomers, the "revolution" was real and obtainable as well as something that was constantly desired and worked for. Student militancy was free and spontaneous and could not be counted on nor was it possible to control or channel into any sort of focused activity. Students wanted to change the world but did not have any particular social, political or economic goal. Their struggle was metaphysical and cosmological. It was revolution in a general sense that they spoke of although not something that would necessarily be directly experienced.[7]

This seeming waywardness confused adult voyeurs who were not sure where style ended and political revolution began. The power and the popularity of the whole movement was all pervasive and gave non-political, non-activist students the idea that they were part of a struggle versus the adult generation and all forms of authority. The mass of youth identified with the ideas of alienation and social resistance demonstrated by the radical few.[8] It is pretty difficult to imagine when one walks through Yorkville today but during the 1960s, it was the primary site in the city of youth culture and its struggle with the preceding generation. On the one side were the hippies led in large part by David DePoe, the community's unofficial mayor. On the other side was the city whose primary effort was to stamp out Yorkville as it existed by "bulldozing it and turning it into a shopping mall."

[1] York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections (ASC), Alan Clarke fonds, Correspondence and subject files - professional series, 2000-015/021(30), "The Debates : Excerpts from Hansard of the debate on Bill C-174, the act which established the Company of Young Canadians", [1966], p. 7.

[2] François Ricard, The Lyric Generation : The Life and Times of the Baby Boomers, Toronto : Stoddart, 1994, pp. 18-19.

[3] Ibid., p. 2.

[4] Ibid., p. 126.

[5] Ibid., p. 119.

[6] Ibid., p. 120.

[7] Ibid., p. 123.

[8] Owram, Doug, Born at the Right Time: The History of the Baby Boom Generation, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996. p. 205.